This article originally appeared in the May 2016 issue of ELLE.

During the summer after my sophomore year of college, my parents and I flew to West Berlin—this was 1987, two years before the Wall came down—to visit my brother, who'd just finished a semester abroad. We toured Berlin, both its freewheeling western democratic half and the eerily retro eastern Communist side, then set off in a massive, brand-new silver BMW—apparently, the utilitarian Opel we'd reserved was out of stock—for a three-week zigzagging family tour of various Eastern Bloc and Western European cities.

With my brother and me in the backseat reverting to childish battles over chocolate bars and radio-tuning rights, and all of us gloating over the ridiculous luck of our automotive upgrade (that car could book), it was in many ways a jolly road trip. But it was also jarring—having lived on my own for two years, I bristled at so much sudden family closeness. And as a Cold War kid raised to suspect the morals and motives of Communism (yet learning in school that America has cranked out plenty of propaganda, too), I felt a confusing stew of fear, scorn, and pity whenever we left the familiarly capitalistic confines of Western Europe and—crossing a border checkpoint where guards invariably scoured every one of our bags (my mom's New Yorker cartoons did not amuse)—ventured into allegedly dangerous "Red" territory.

Visiting a stately industrial-design museum in East Berlin, I could have laughed and cried contemplating a drab gray rubberized raincoat proudly on display, and beside it, a package of state-issued juice-in-a- pouch. This is the best you guys got? I thought to myself while taking pains to maintain a flat affect, so as not to offend the stone-faced guards. When we passed through a tiny East German town a couple of days later, however, I couldn't help choking up. A group of young people were sunbathing nude beside an uninviting shallow lake across the road from a coal-powered manufacturing plant—the kind that had already long been banned in the U.S.—exposing every inch of their pale, skinny bodies to the dangerously sooty air. The weird, sad scene embodied the complacent deprivation that I imagined was the lot of everyone reared in the Eastern Bloc.

Really, though, what did I know? About anything? Easy for me to speculate about the skinny-dippers' inner lives as we blew through their town. I realized I was brashly projecting assumptions onto total strangers. I needed time alone to sort out my mind and get a better bead on these foreign places and their people. A few hours later, in Prague, I spotted a hair salon near our hotel; beauty shops have always been places of refuge and emotional refreshment for me. Like our hotel, a palatial place gone somewhat threadbare, the salon had an aura of faded glory. Its name was written on the front window in fancy gilt Czech, which I couldn't read, but a pair of needle-sharp scissors below made its purpose perfectly clear. Those golden shears, gleaming in the late-day sun—plus the appealing thought that altering my physical appearance might open up space for change inside—beckoned to me. I begged off from a family walk, claiming my thick, midback-length hair was stifling in the summer heat, and before anyone could protest too forcefully, I zipped back to the shop on my own.

I was very nervous pulling open the door: Here I was, giving myself up to the other side, come what may. But the heavyset middle-aged woman in the salon—sweeping up at the end of the day in a sleeveless flowered shift—eased my fear immediately. She smiled and shrugged when she understood that language wasn't going to work for us, and nodded vigorously when I pantomimed suffering in the heat as a result of my heavy hair and held up my ends to indicate the three or so inches I wanted trimmed. Once the woman started snipping, she lifted a big hank of my hair, pretending it was like hoisting a barbell and puffing out her cheeks to demonstrate her now firsthand appreciation of its heft. I rolled my eyes in the mirror, hoping to convey "tell me about it." She threw back her head and laughed—to my great delight. We passed the rest of our time together grinning whenever our eyes met, both a little surprised (I was, anyway) to have found each other such good company.

Though I could have quit after that first clean-lined trim—exactly what I'd asked for—I enjoyed that funny Prague salon so much that I decided to make it my mission to stop in every city we visited for a new haircut. I sold the idea to my family, travelers who believe in leaving no museum unturned, as a kind of sociological exploration: I wanted to see what was happening inside the salons, what hairstyles they were

pushing, and since these were plainly pretty safe places (even if not typically visited by tourists), they let me skip some museums to pursue my plan. In Vienna, I peeled off and got a rather too severe shoulder-length bob at a busy salon cranking Falco (Vienna's only international techno-pop star), where all the staff were rather too severely dressed in black leather uniforms, despite the heat. At a simple three-chair beauty shop high atop a hill in Salzburg, a young woman skillfully thinned and tapered my arty Viennese bob. Her English was excellent (a nice break from the made-up sign language I'd had to rely on elsewhere), and when we discovered we were both big vintage fans, she drew me a map to her favorite thrift shop. Big score: When my brother and I later visited the shop, he bought a pair of absurdly brief lederhosen and I bought a silver-buttoned dirndl vest that remains a staple in my wardrobe.

We veered south to Trieste, from which distant relatives on my mom's side emigrated more than a century ago, and where, in my long-lost ancestors' honor, I entrusted my hair to a heavily perfumed man at a seaside barber shop crawling with cats. Despite his insouciant promise to replicate Debbie Harry's pretty/messy chop in a picture I'd ripped out of a magazine—nessun problema—I received an entirely non-Blondie mullet that amused my family no end. From there, we moved on to Bratislava, a slightly down-at-heel city dotted with boarded-up shops that must have had hipster aspirations at some point in the '70s. Our hotel rooms had beds set on groovy raised platforms and burnt-orange shag carpeting curling up the base of curiously curved walls. Touchingly, when I made my way to a beauty salon on the main drag there, I found proof that locals' interest in bold modern aestheticism was still hanging in there.

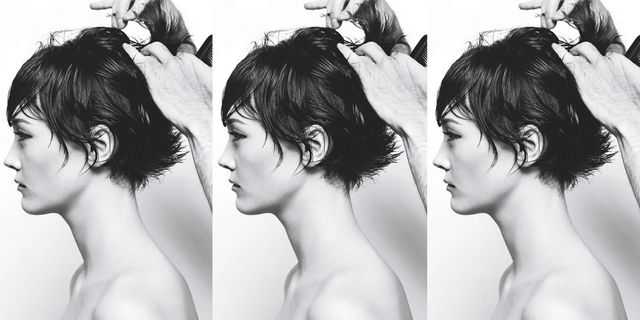

The walls of the shop were decorated with silk-screen posters of women with stand-up Mohawks—clearly the house style (the young woman who led me to her chair had a jagged punkish cut herself). I pointed to the women on the wall, then to my own head. Wordlessly, my stylist nodded and got to work. Suddenly, a woman burst into the salon—she seemed to know both the employees and the clients—and excitedly told a story about a straying boyfriend, or so I suspected, based on the way fury and hurt both played across her red face (I'd been there once with a cheater myself). Throughout her long diatribe peppered with exclamations (Slovakian expletives? I sure hoped so!), her friends clucked and groaned sympathetically. Eventually she calmed down, and when others picked up the conversational thread, she even laughed a bit at their tales, told with gusto, it seemed, to distract the aggrieved visitor from her own travails.

The whole scene was deeply moving to me. I could easily imagine a parallel version of all this animated, entertaining talk occurring among my friends back home. As my remaining hair fell away in startlingly long chunks—I hadn't realized I still had that much to chop—I felt proud to have found a way to collect some intimate data on the women I'd encountered on this trip: Curling photos of kids and pets and backpacking trips tucked into mirror frames, homemade lunches I occasionally caught them eating midday, and the rising and falling inflections of languages foreign to me—each spoke volumes about basic, and beautifully universal, human needs. Even today, when political and cultural differences can once again seem unbridgeably wide, reflecting back on these salons—where fans gently wafted hairspray-scented air, summer light filtered in hazily from the streets, and I was deeply reassured to find that most people are intelligent and kind, when you get to know them a little bit—I feel my heart beat more slowly and my fears of unknown others fade. That day in Bratislava, I leaned all the way back in my plastic swivel chair, relishing the new ease and understanding I'd acquired spending time around people I wouldn't otherwise have had a chance to meet.

That night, over dinner with my family at an outdoor café, I couldn't stop running my fingers through my new short-back-and-sides Bratislavan brush cut, giddy with the self-surprise of actually going all the way—of becoming a close-cropped girl, something I'd never been before. Boys my age promenading down the street past our café did not give me a second look, I'll admit. Yet rather than feel dejected, I took their hey-whatever attitude toward me and my new hair as a positive sign: I'd finally shed some of my overt foreignness and was blending in well with the local scenery—just one more cosmopolitan citizen of the world. And as we devoured delicious goulash, a thick layer of grease floating on its surface, for the equivalent of 99 cents U.S. (no doubt a far cry from what you'd pay for soup in Bratislava today), I was thrilled to find, atop my head, a tangible take-home record of my earnest stylist's vision of art-forward fashion, and of my own intrepid instinct to break away from the usual tourist routes—the best souvenir of the trip.