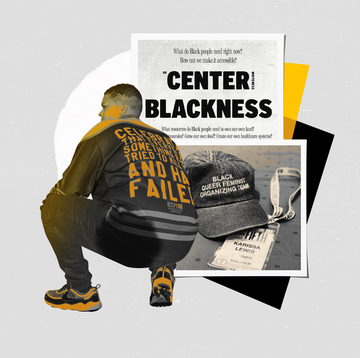

EDITOR'S NOTE: Many hairstylists are not required to learn how to style, cut, and color Black hair in school—resulting in racial segregation at salons across this country. The writer of this story is a director at one such segregated salon and is still employed, so we chose to keep her identity and that of the salon private for her personal protection. Her experience is not uncommon, though, so we urge you to ask your salon about its policies and demand that it ensures hair equality by hiring those equipped with the knowledge of working with Black hair.

When I became the studio coordinator at a top salon, I didn’t initially feel out of place among a largely White staff. Growing up in a big city and attending a predominantly White all-girls school, I was accustomed to situations in which I was surrounded by those who shared skin tones and ideologies different from me. Being the only Black person in a room was an everyday occurrence. I grew comfortable in these situations, able to navigate the nuances of what seems affixed to the DNA of America. I quickly realized that my tolerance ends when I’m exposed to moments of racism, whether overt or veiled. Which is why I soon became uncomfortable in my own skin at the salon, where I learned that racial segregation never really ended.

Racial inequality has become a forefront of conversation in today’s political climate. And although people will get defensive, clutch their pearls, and deny it when you call them out on racism or white privilege, now, more than ever, we need to have these uncomfortable conversations. Just because something is commonplace does not make it okay. Especially when an unjust practice—hair discrimination—is brought to your attention and you still choose not to change.

As I sat at the salon’s front desk on my third day, receiving training on the procedures and scheduling, I was introduced to the wait list. With 1,000-plus people and stylist books that were completely filled for the next three months, the level of elite exclusivity became clear to me. At first, admittedly, I saw this as praiseworthy news. This was a small business with a dedicated base of customers willing to wait nearly a year to get their hair transformed at the hands of trained professionals. But as I scrolled, continuing to examine the queue, another reality brazenly came into view: As if typed out of habit, every client with Black hair in their profile had the word NO beside their name in big, bold, all-caps letters. I coyly made eye contact with the person training me. “No one here knows how to do African-American hair,” they instinctively replied.

Though I was taken aback, part of me attempted to rationalize their answer by reflecting on the hair and salon industry as a whole. Many stylists are not required to be trained in all textures, and many salons don’t employ those who know how to work with curly, coiled, and textured hair. This is entirely unacceptable. Some salon owners and stylists assume the stereotype that Black hair is unmanageable, while others just blatantly refuse service.

I let it go, at least momentarily, and I gave the job a chance. The recent birth of my daughter coincided with months of unemployment, so the prospect of stability flew directly in the face of my own ethical tenets. I took the blessing for what it was, and as institutions have always hoped, I kept my mouth shut and my head down. After all, women of color are made to think that they don’t deserve a seat at the table. If they do get one, they’re expected to shut up and eat quietly, because they are there for show.

I can now confidently say, after almost two years and a promotion to director, the salon I work for does not welcome Black patrons. Our policy requires that all new clients send in a picture of their hair to get on the wait list. And since the beginning of my employment, I have outright been told to send Black women—textured hair or not—to the Black-owned salon down the street. Over the years, I’ve constantly grappled with this. When I open an email from a beautiful brown woman who looks like me and I have to tell her we don’t see people like you, it hurts my heart. Have I become a pawn of a prejudicial institution? Am I further propagating racial biases, and, in regard to my employment, am I complicit? Though I can’t publicly name the salon due to my employment at this time, this issue is bigger than just the one place I work. Discriminatory hair practices disguised as ignorance are common in many salons servicing predominantly White neighborhoods.

To be clear, my salon does have clients of Indian, Latina, and Asian descent. The owner might see that as inclusive, but it’s no longer good enough for me. You cannot be somewhat inclusive—either you are, or you are not. You can’t completely bar an entire race from your establishment due to inadequate training, and then defend your actions with clichéd rebuttals like, “I have friends or employees of color.” Adjacency does not imply allyship. And in this case, my salon is assuming that the few cases of textured hair it tends to outweigh the hundreds it so blatantly denies.

Saying that no one can “do Black hair” is an unacceptable cop-out when the owner has given me, a Black woman, highlights. It’s a lie. There are plenty of White women with curly, coarse, thick hair who are able to have their strands colored here at the salon. So what is the excuse again?

I have pleaded to diversify the clientele of the business, but the request falls on deaf ears. It’s painful to know that I would be sent down the street to a different salon for a treatment if I didn’t already work here. We have Black employees, but no Black customers. Often people of color and, more specifically, Black women are held back in environments that masquerade as something they are not. They include us only under the guise of diversity and equality as an obligation to prove that they are progressive. Prejudice is oppression, no matter the magnitude.

When clients email and ask why they see only blonde women on our Instagram, I’m ashamed to have to fabricate an answer that doesn’t disclose the full truth—that I work for a business so blatant in its disrespect for Black women. My race of women. I can no longer be silent. When you strive to be the best at what you do, it should be a given that you seek education to perform your craft for all people. There are numerous courses and schools that can teach stylists how to dye textured hair, especially when they take classes on cut and color techniques often enough. Stop saying you don’t know how to do Black hair and say what you mean: You don’t want to do Black hair. Whether you can or cannot is of no consequence. Once upon a time, you couldn’t do hair at all.

I can only change the racism in the world by doing what I can to dismantle the racism within my bubble. I’m asking all salons and stylists today: Please seek the education needed to include all women in your craft. There have been incredible strides made in the beauty industry toward diversity, like inclusive foundations and skin care targeted to darker complexions. It’s not enough. Every business—more specifically, hair salons and cosmetology schools—should be inclusive of all people.

This ignorant and blatant segregation of hair types is all too common in salons around the world, even as institutions have worked toward equality. This modern-day segregation can’t be normalized or swept under the rug. We must continue to fight the invisible, Jim Crow–inspired signs we see, if not just to combat the generational trauma they inspire. If you are White, the next time you’re sunken into your salon chair, please ask your stylist, “Do you do Black hair?” And don’t take no for an answer.